#4/120 - It's never too late - The most dangerous creative block isn't lack of talent—it's the myth that you've missed your window.

If you dream of creating something original and meaningful but worry that it might be too late to start, this essay is for you.

I believe we all have ambitions and desires to create something, regardless of scale—whether it's taking people to the moon, filming videos to share our journeys, drawing rural landscapes as gifts, or growing vegetables to share with our community. These activities are all driven by the same motivation: a desire to create.

However, we're often confronted by the harsh reality. Deep in our mind, we believe that most of us can't easily sustain ourselves through these creative pursuits and their outcomes.

We hesitate, understanding that a creative journey requires time and space, along with practice and skill to accomplish our goals. All of this demands significant effort.

Here, classic overthinking kicks in. A seemingly wise voice whispers in our ear, "Let's think about the opportunity cost." What if we fail? What if our hard work doesn't pay off? This voice hinders our progress and creates a false sense of security, encouraging us to stay within our comfort zone, use familiar tools, and avoid risks. Then we regularly use "It's too late" as an excuse, it's simple and reinforced by the general public. You are too old to start learning, and you are too late from the competition.

This mindset is dangerous. If you have the drive and ambition to create, but choose the safe path instead of taking calculated risks and making the necessary effort, you may feel temporarily wise and secure. However, this is an illusion. Over time, this sense of security becomes less self-affirming, slowly cultivating deep regret. Thoughts like "What if I had learned it sooner?" or "What if I had begun earlier?" begin to surface. For creative people, this can develop into resentment that harms their mentality. Instead of focusing on building their creative process, they become fixated on results—something not entirely within their control.

Let me tell a story which has profound influence on me around this topic.

Tell me the thing you are going to build

She started painting at age 72

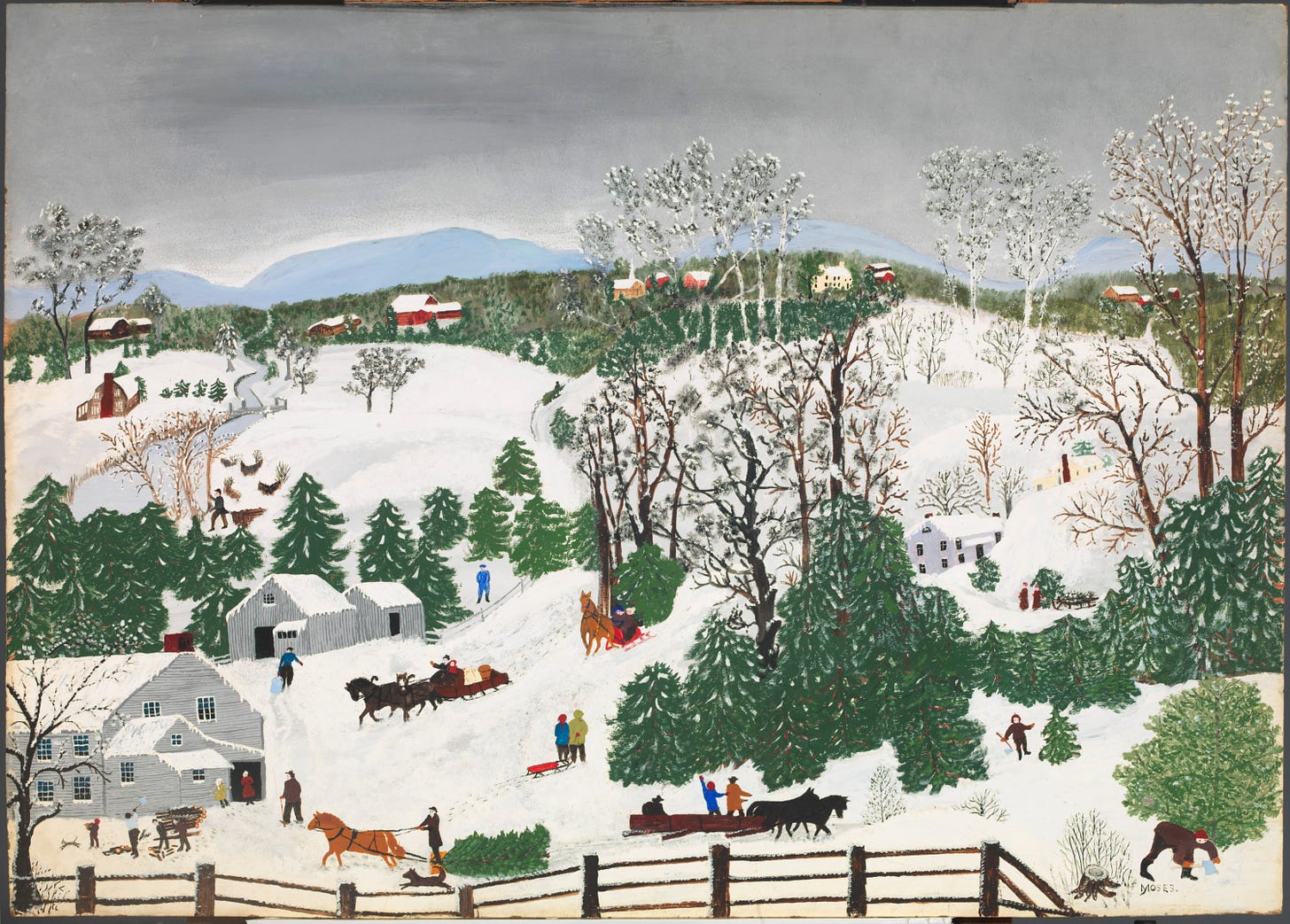

She was born on a farm in Washington County, New York. The area spans miles of vast farming land where Victorian storefronts and Federal-style buildings blend together to create a distinctive landscape. She grew up with four sisters and five brothers. As a child, she began painting with whatever materials she could find: flour paste, slack lime, ground ocher, twigs, grass, and bark—using these common materials to capture the landscapes in her mind.

To help support her family, she began working at age 12, serving several wealthy families as a housekeeper and cook. She earned a reputation as the best working girl in the county.1 Although she expressed a love for painting at a young age, she rarely had time to pursue it. At 27, she married farmer Thomas Moses and bore 10 children, five of whom died in infancy. Her adult life was consumed by her duties as a farmwife. For three-quarters of her 101 years, art remained a luxury she couldn't afford.

As she aged and her farm duties lessened, she channeled her energy into creating gifts, transforming potential waste into decorative pieces for family and friends. At 58, she used house paint to decorate a fireboard. At 72, while caring for her daughter Anna, who was suffering from tuberculosis, Anna showed her a picture made of yarn and challenged her to duplicate it. This inspired her to begin stitching what she called "worsted" pictures, giving them away to anyone who would accept them. Her sense of accomplishment came from her ability to make "something from nothing."

Later, when arthritis began to trouble her, her sister suggested she try painting. "I did not want my pictures to be eaten by moths, so when my sister, who had taken lessons in art, suggested I try working in oils, I thought it was a good idea. I started in and found that it kept me busy and out of mischief."2 Even then, she didn't consider her creations serious artwork, viewing them simply as gifts that were easier to store and share.

As her collection of artwork grew, she began to develop artistic ambitions and seek recognition beyond her immediate circle. She entered some pieces in the Cambridge county fair, alongside her canned fruits and jams. "I won a prize for my fruit and jam," she sardonically noted, "but no pictures." This changed during Easter week of 1938, when New York art collector Louis Caldor noticed her paintings in a small drugstore. He purchased all of them and sought to introduce her work to the public.

It was in 1940, at the age of 80, 20 years after her art creation journey, Grandma Moses held her first solo exhibition. Later she became one of the well-known household names in the USA.

Survivorship bias then what

I can foresee someone arguing that including this single story represents survivorship bias. Let's examine this potential argument. First, this is just one example highlighting the possibility of late-starter achievement. Second, what if Grandma Moses simply had natural talent, and what if it was pure luck that an art collector happened to visit that small drugstore and chance upon her painting?

While these arguments are partially true, they miss the true metaphor of Grandma Moses's story. Waving the flag of survivorship bias didn't help us see the forest for the trees. I deliberately chose to present this story alone because I found it insightful not merely as a success story, but because of how it unfolded.

Let me explain my reasoning.

She was truly a late starter. Although many biographies emphasize her interest in painting during her youth, I would argue this is deliberate hindsight bias - people's desire to see a head-start story. It wasn't until age 72 that she began oil painting. Based on available materials, she didn't pursue traditional success at the start; she simply wanted to create gifts for people in her community. She used whatever materials were at hand and painted scenes familiar to her community - farming, rural life, seasonal changes.

When arthritis struck, she didn't stubbornly cling to her familiar materials and tools but quickly adapted to new ones. Even then, her focus remained on creating art for her family and community. She practiced consistently and persistently. This artistic journey became her life. 'If I hadn't started painting, I would have raised chickens,' she would say. Or, upon further reflection, 'I would have rented a room in the city and given pancake suppers.3 For her, art became an essential element of her life—whether successful or not, she did it to make herself happy.

In her journey I saw three valuable lessons.

The first one is the importance of creating something meaningful for our community from the start. Our community is where we belong and draw energy from, and giving back to it provides a fulfilling sense of purpose. This feeling can serve as fuel for your creative journey.

The second lesson is about adaptability: when the time comes, don't be afraid to switch from tools you're familiar with. Better yet, try many tools before committing to any single one.

The final lesson is cliché but true: enjoy the journey. However, this isn't as simple as it sounds. The creative journey isn't like a vacation where you can relax; it's often challenging and sometimes disturbing. During nights of being underrecognized, when self-doubt creeps in, or when opportunities suddenly vanish – these are the true tests that the journey presents.

Throughout all these practical lessons. There is one thing that those who highlight survivorship bias can not fully comprehend. For me that is truly the essence of this story.

It's never too late to create something meaningful.

Your Present Age is the Perfect Starting Point for Creativity

Making connections is the core theme of this newsletter. While crafting my investment strategy, something significant caught my attention.

To cope with risk in investment, some investors champion value investing and the power of staying in the game. This means not trying to "time the market" or relying on technical analysis to determine when to invest. Instead, you find an overlooked but valuable target and consistently invest in it regardless of timing or price.4

We can apply this same approach to our creative journey, which demands significant time and effort. We ourselves, before being recognized, are the most overlooked yet valuable assets. What we need to do is no matter how old we are, how not well-equipped we are, how low status we are, we keep investing, keep doing what we think is valuable and creative.

Though the future may be dim and unknown, filled with instability, danger, and unfriendly events. Rather than simply believing the result will be great, we can choose to believe that the experience itself is invaluable.

It's never too late to create.

Thanks

Thanks Jonathan, Jimmy, Lucy, Shaka for reading the draft of this article. I can not make this far without your help.

Arnold B. Cheyney (January 1, 1998). People of Purpose: 80 People Who Have Made a Difference

S. J. Woolf, New York Times Magazine, December 2, 1945

Anna Mary Robertson ("Grandma") Moses Biography. Galerie St. Etienne. Retrieved August 30, 2014

It's called dollar cost average strategy